“(Wabi-sabi is) a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble. It is a beauty of things unconventional.”

—Leonard Koren

When most Japanese persons are asked to explain what wabi-sabi is, “they’ll shake their head, hesitate, and offer a few apologetic words about how difficult it is to explain.” [ 1 ] Koren claims that this is because Japanese persons “have never learned about wabi-sabi in intellectual terms.” [ 1 ] I largely disagree with him—I believe that describing wabi-sabi in a manner that removes the context of Japanese culture—besides historical ones—is frankly a disservice to the philosophy at worst and a source of at least some misunderstanding at best. Given the interconnection of wabi-sabi as a set of ideals and Japanese culture as a whole, reducing wabi-sabi to the former is to thereby describe a philosophy that may have many elements of wabi-sabi, however, can’t truly be wabi-sabi in the Japanese sense of the word precisely because it lacks the baggage of Japanese culture and its associated language, history, and manners of understanding the world.

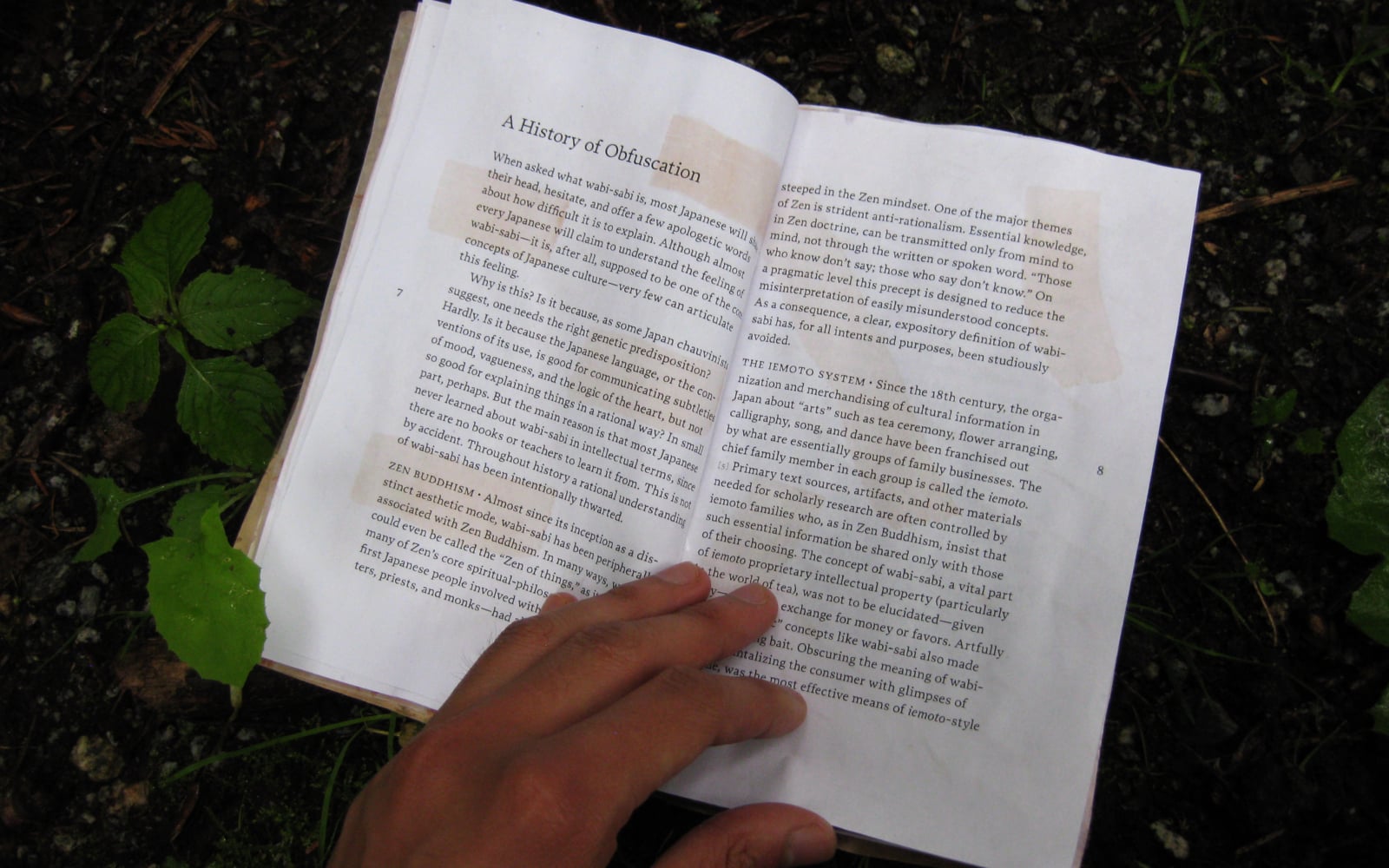

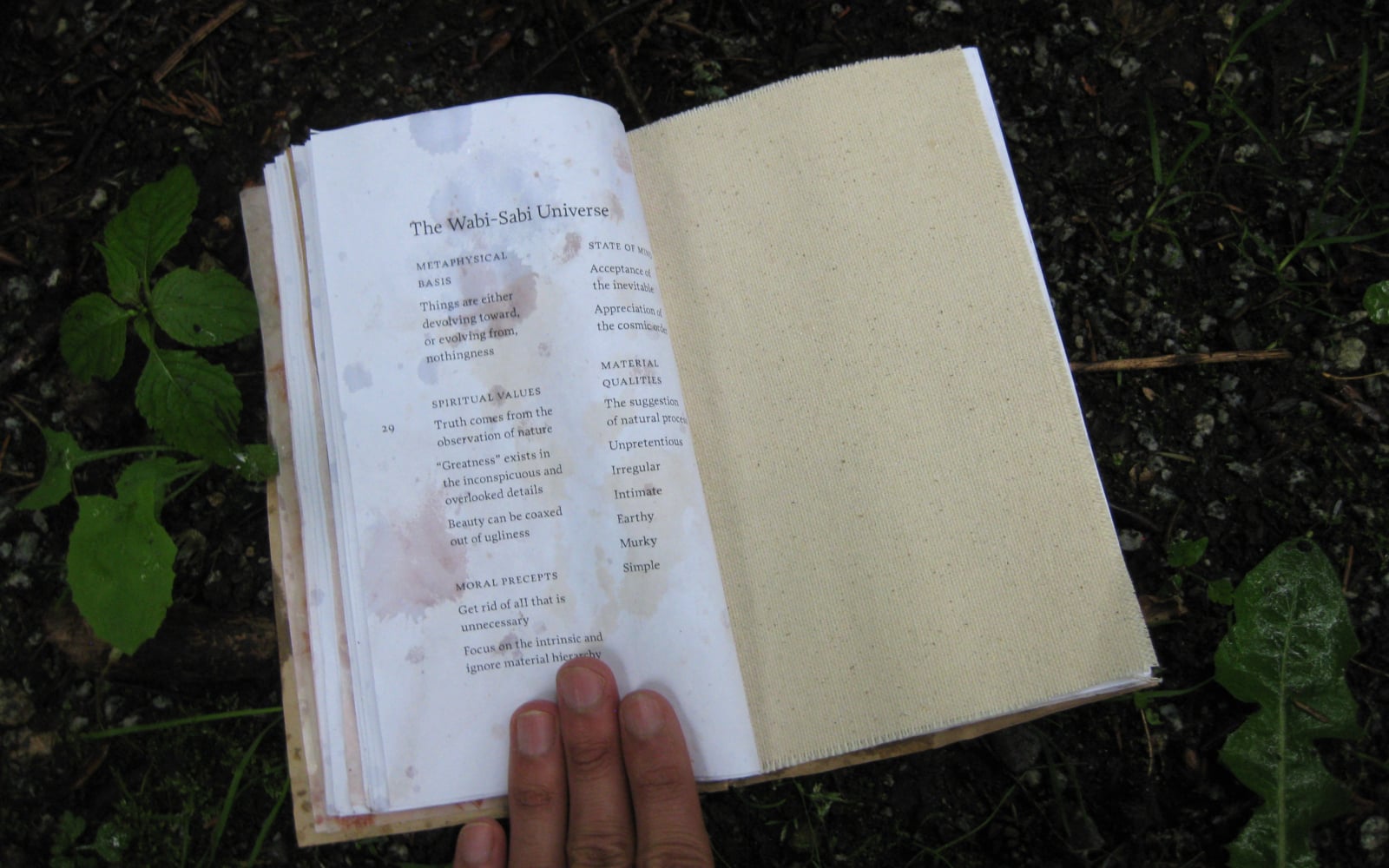

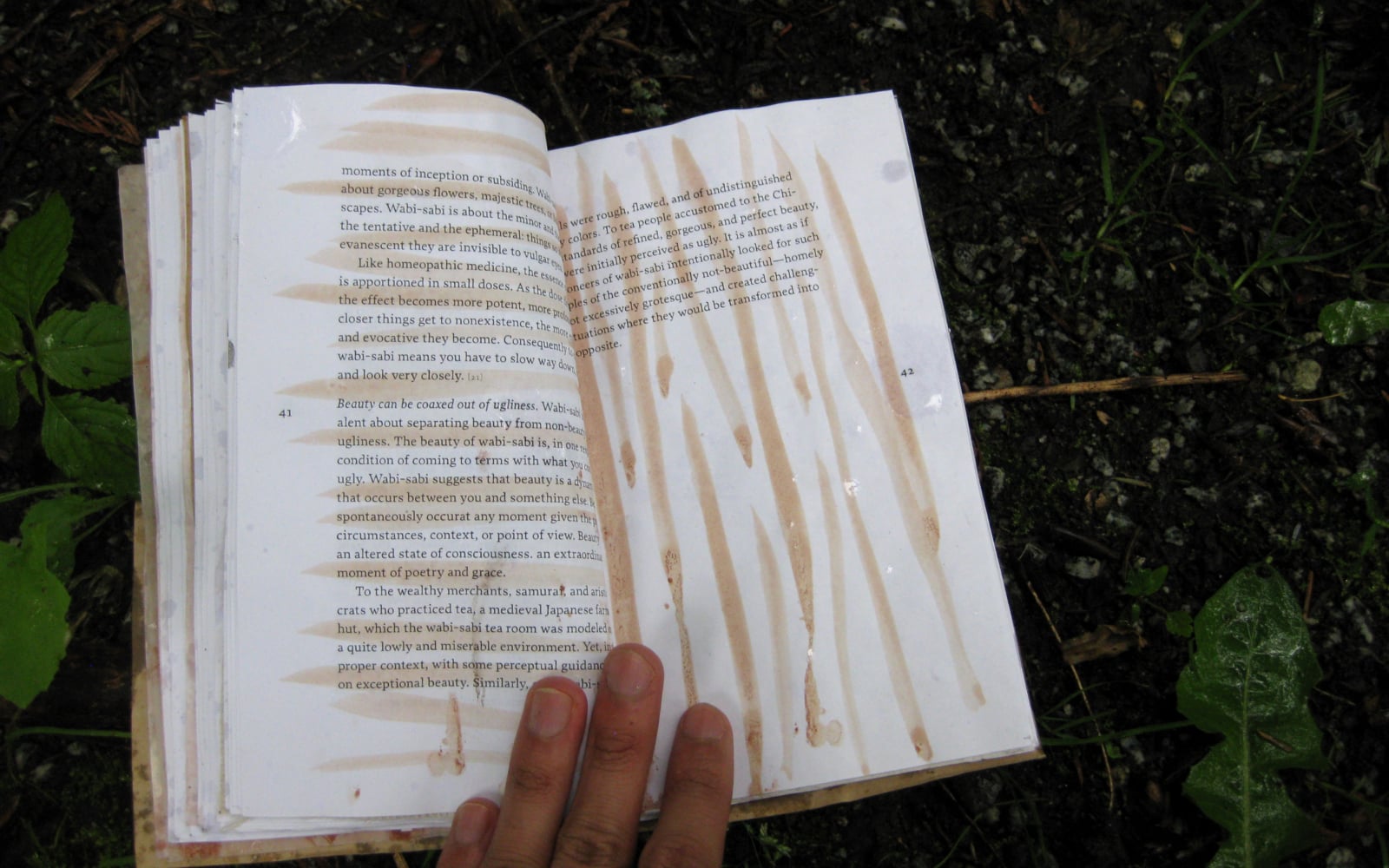

I largely ignored the book upon my first reading until that following summer where I worked in wilderness of BC, Canada, [ 2 ] where I lived in a tent several months to slave away working 9–12 hours a day, seven days a week. Needless to say, no luxuries were included: no showers, toilets, running water, or internet. [ 3 ] As cliche as it is to mention, it taught me how little is required for a human being to survive. The values of the book started to come back to as I began to realize that the largest flaws of the book was not so much its content—which for its faults, had some merit—as much as the book as a physical object and its associated book design. Wabi-sabi is not something that can merely be told trough a book alone. It is something that needs to be learned trough complete embodiment; it requires an entire culture, underlying system, and society. It is a lifestyle, namely something that requires a small scale, more communal, and more hand-crafted society compared to the book as a large-sized, glue-bound, mass-produced object. Moreover, the book design felt very cold. The typography was set at a giant size and it was the first time I’ve seen a Humanist sans-serif in a large size with massive leading be so illegible. In addition, interjected between chapters are photographs of objects that the author believes have the quality of wabi-sabi, which are supplemented with his own commentary.

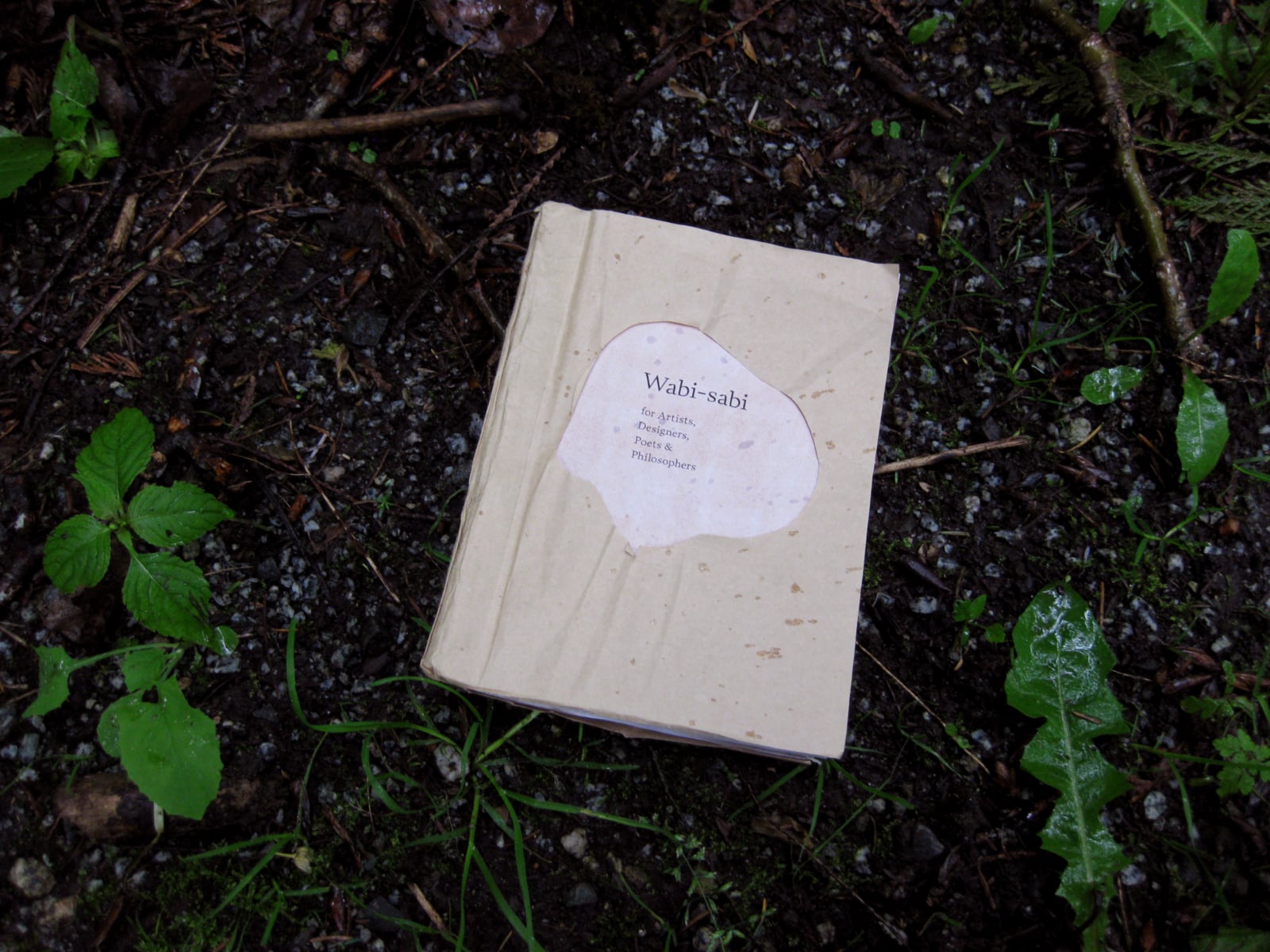

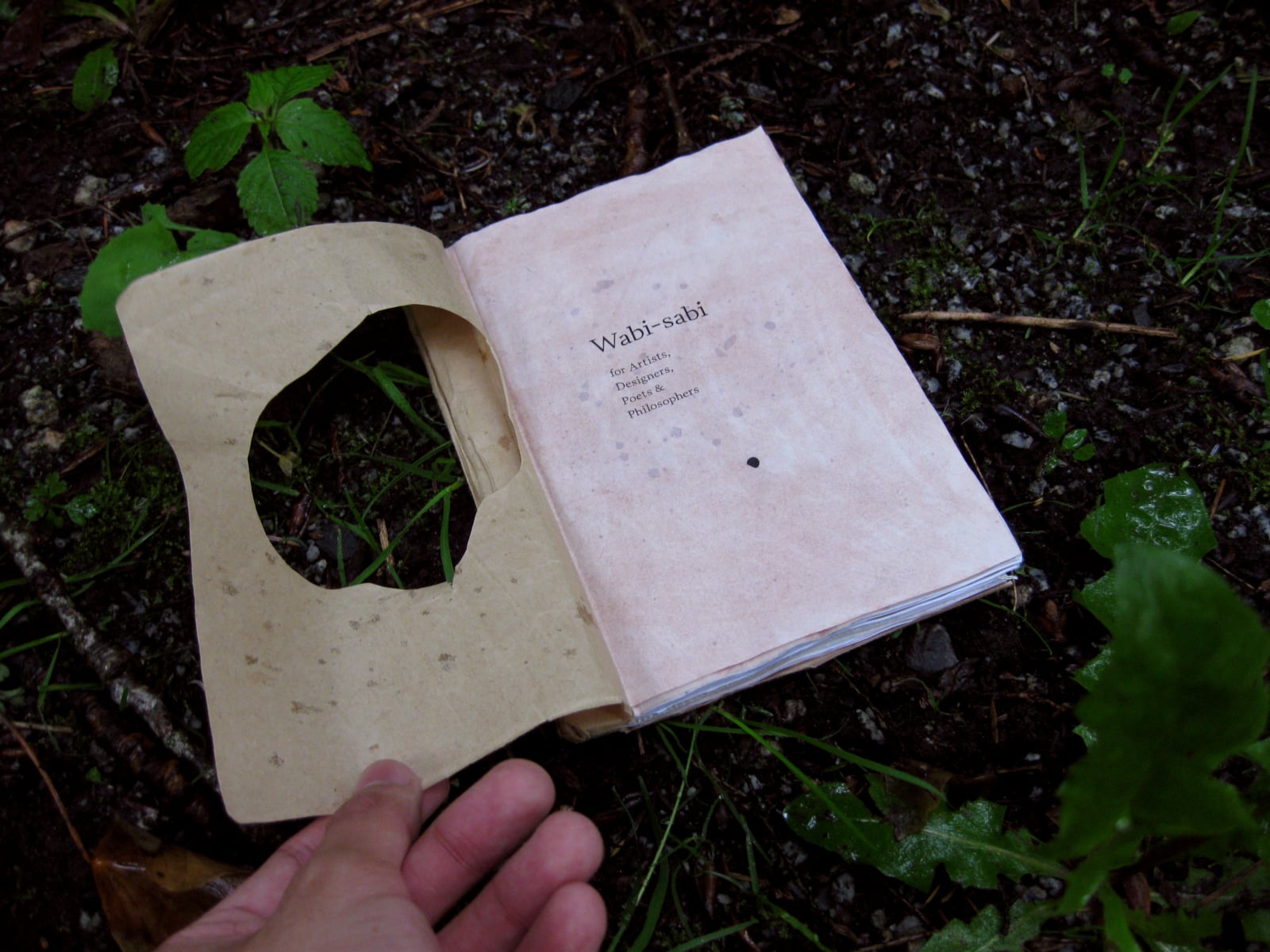

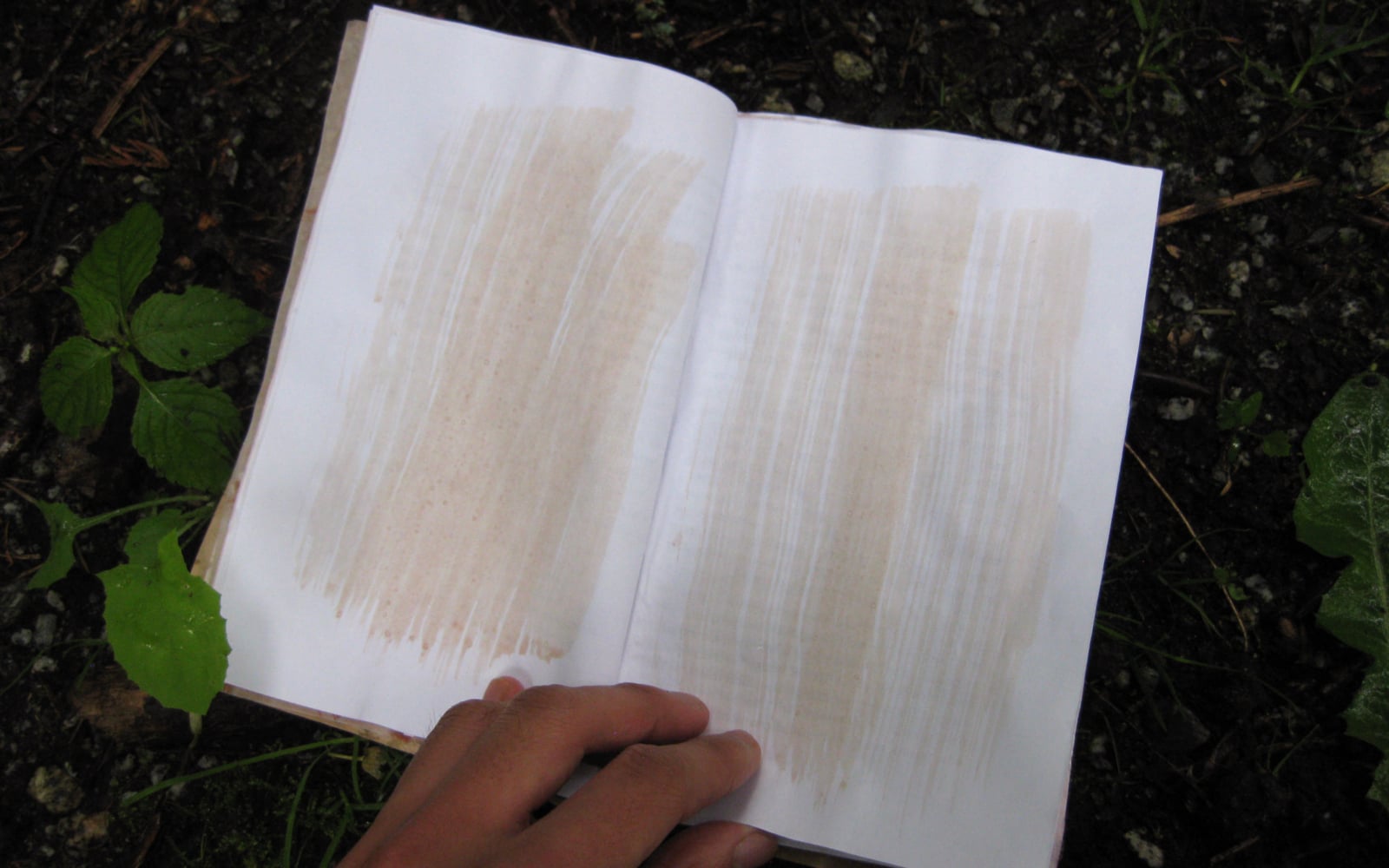

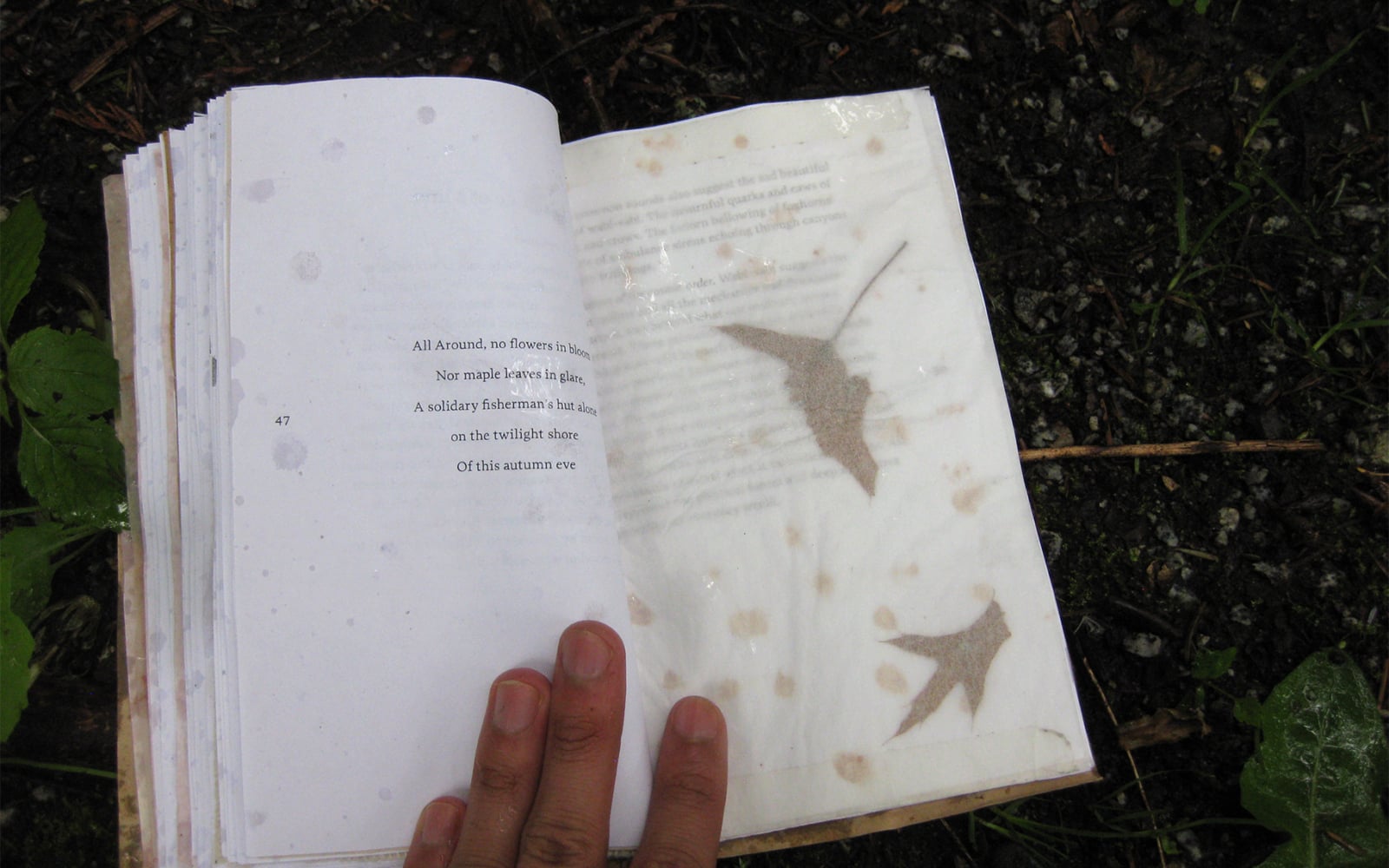

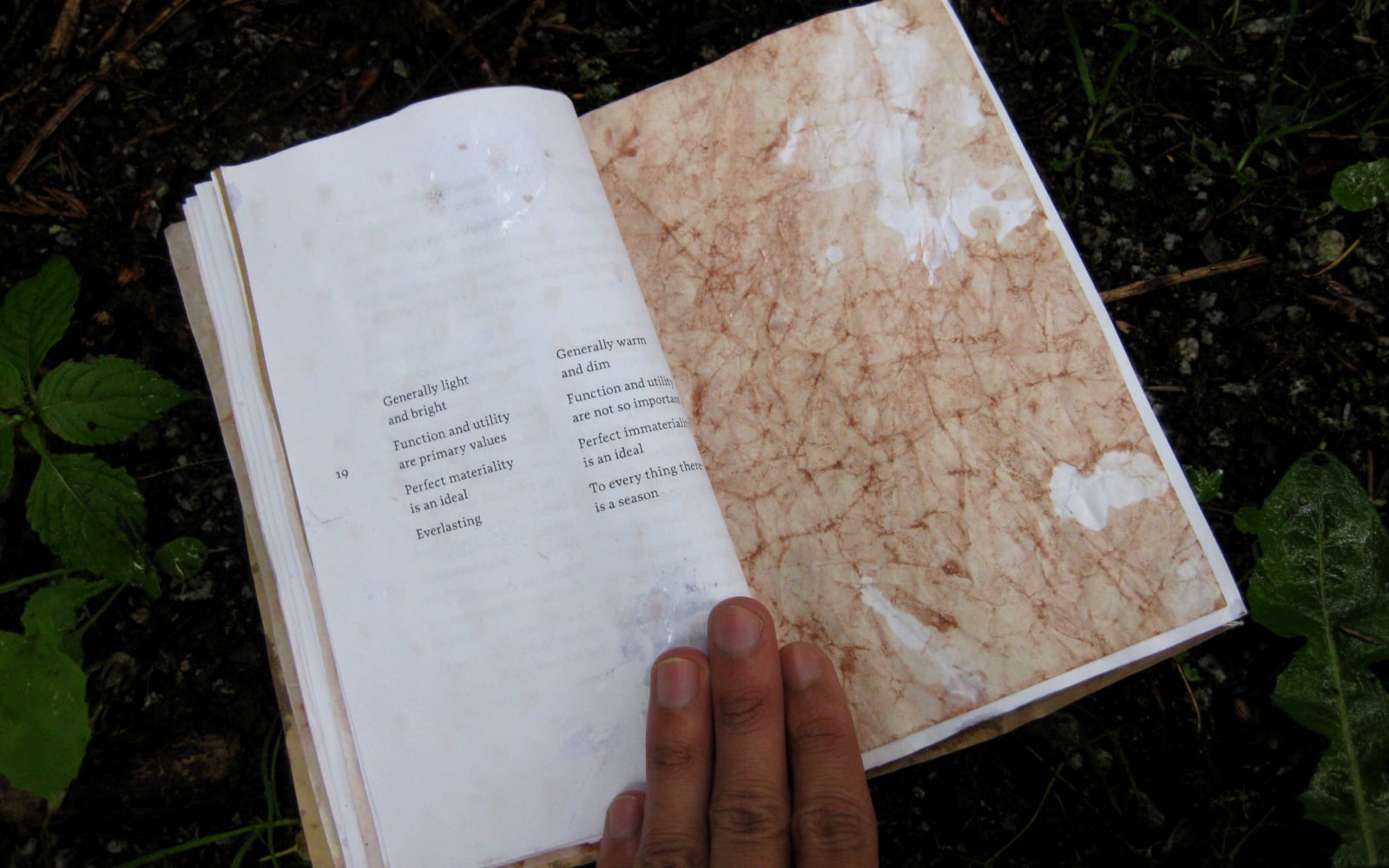

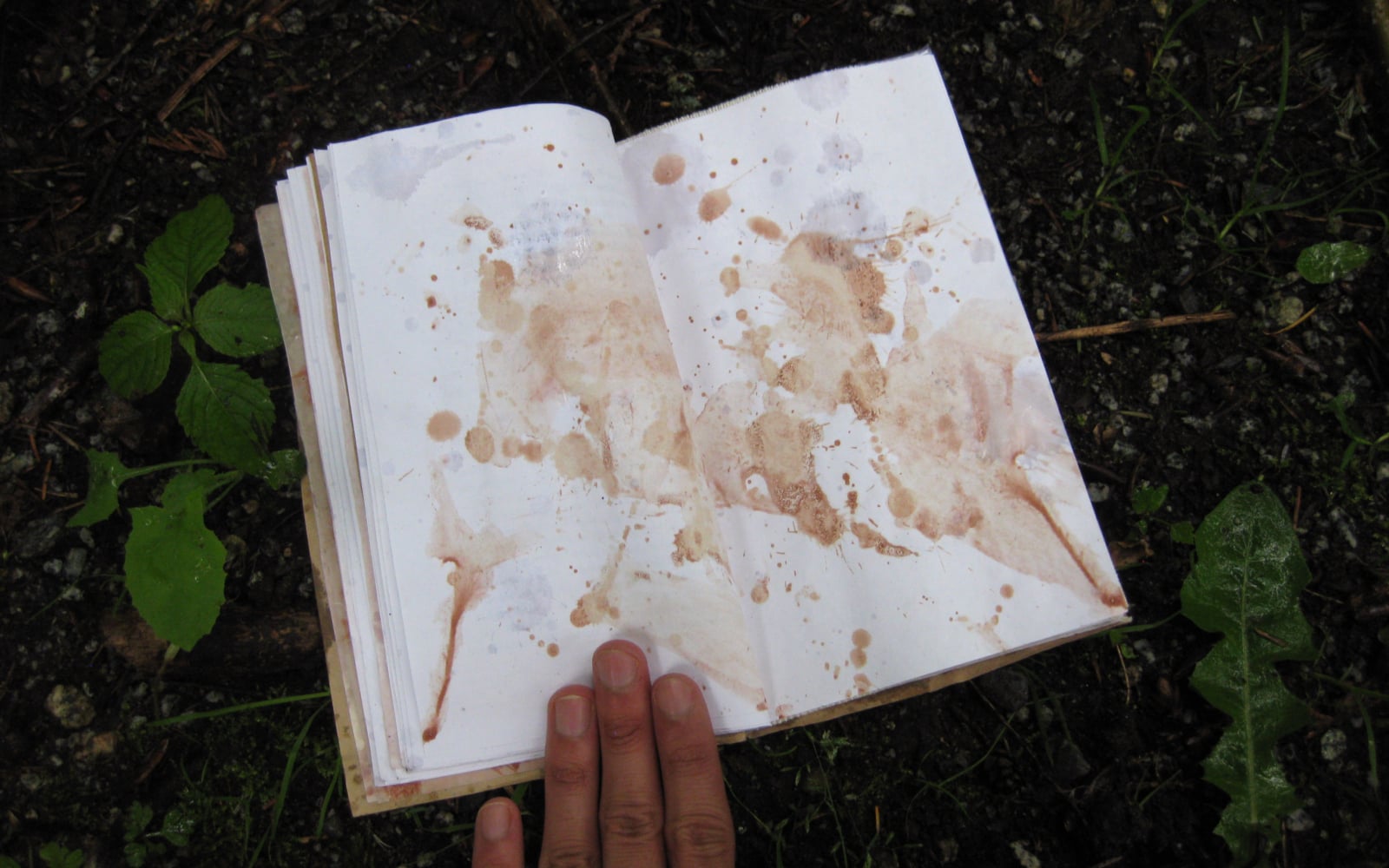

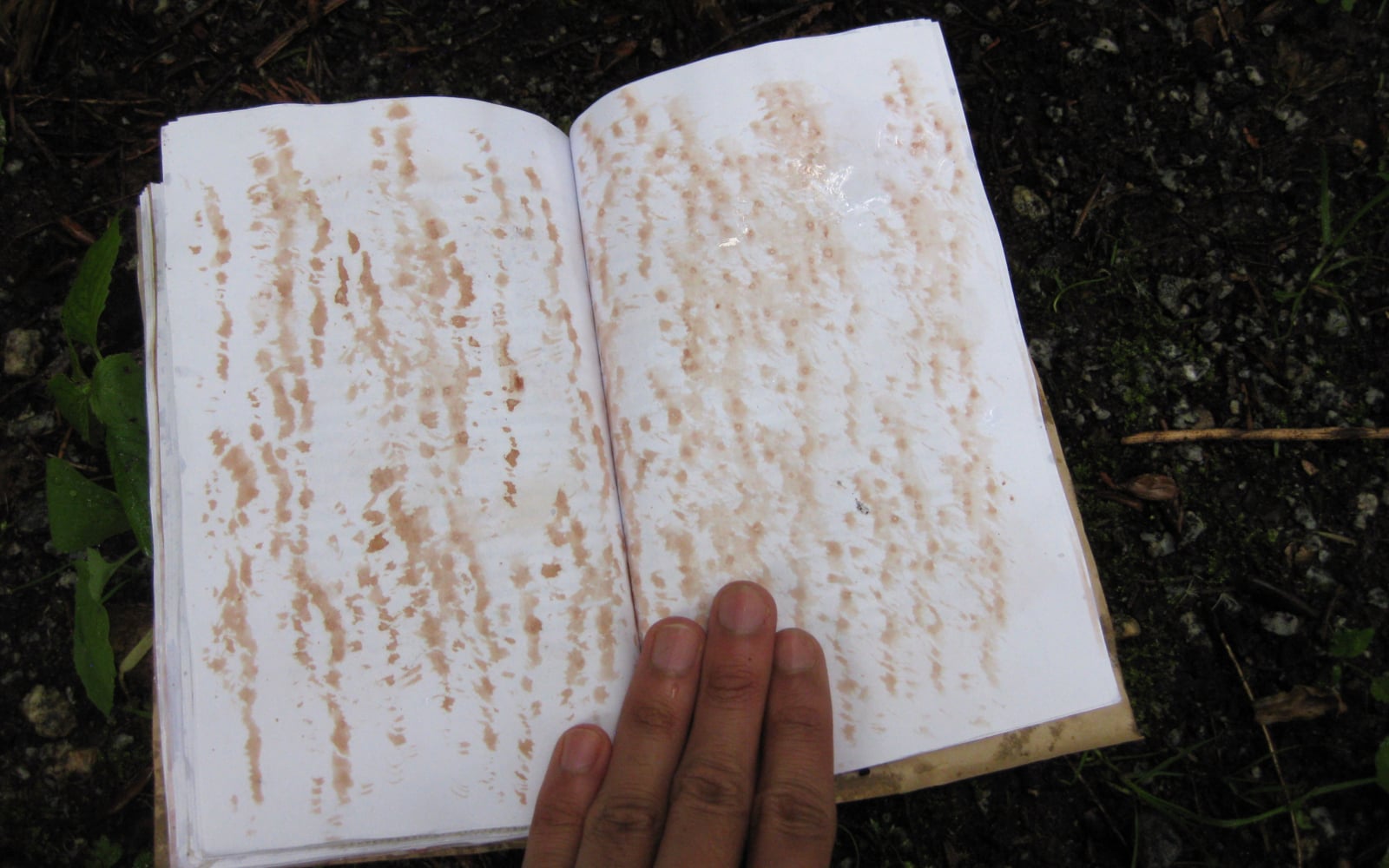

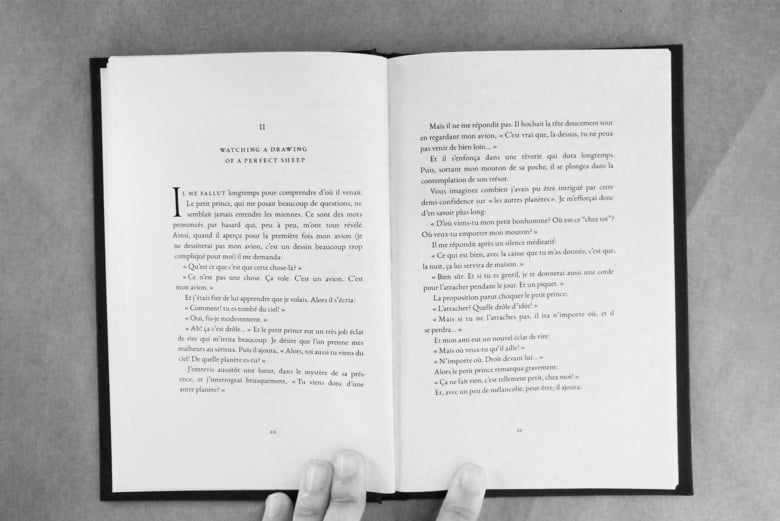

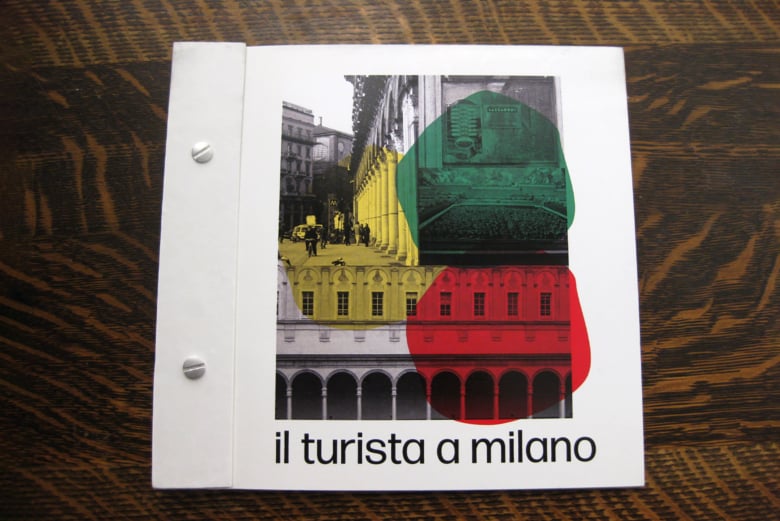

I decided that the best way to understand wabi-sabi, was trough the act of craft. I tried to design something that hopefully resembled wabi-sabi a little more authentically. I aimed at something smaller and intimate following the tinier Japanese book sizing standards. The book was assembled by hand with the most mundane and humble materials. In place of a higher quality paper stock for the outer pages, a lower-quality one was chosen: craft paper. In place of photographs that the author imposes on the reader as objects of wabi-sabi, I thought that it should be the reader that should come to their own subjective understanding of what is and isn’t wabi-sabi. The pages between chapters would be ones weathered down by folds, cuts, and water damage, that—in any other scenario—would be disregarded as a sign of a worn-down and used novel read a thousand times. [ 4 ]

Ultimately, this story of a book’s ignorance is also one of my own. Despite this project, I still admit that my understanding of this topic is very shallow. The idea that one can quickly master a philosophy in a manner of days or months with no prior experience or background is nothing but a Hollywood fantasy, but the least I can do is broaden my own understanding to a way of living I wasn’t as aware of before, even if it’s miniscule. Maybe, just maybe, there is an unexpected virtue in ignorance, with the right intentions.

footnotes

- [ 1 ] From Wabi-sabi: for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers.↲

- [ 2 ] Specifically, it was a morel drying camp.↲

- [ 3 ] It was just myself lacking internet actually, as I lacked a data plan for my phone at that time.↲

- [ 4 ] For the record, I do believe that a battered down used paperback is the proper way to read most older novels. It feels wrong to read a new edition of anything by Orwell, Kafka, Kerouac or Kundera on top of my head.↲